Thylacine

Tasmanian Tiger, Tasmanian Wolf

What is a Thylacine?

The Thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus: dog-headed pouched-dog) is a large carnivorous marsupial now believed to be extinct. It was the only member of the family Thylacinidae to survive into modern times.

It is also known as the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf.

What did it look like?

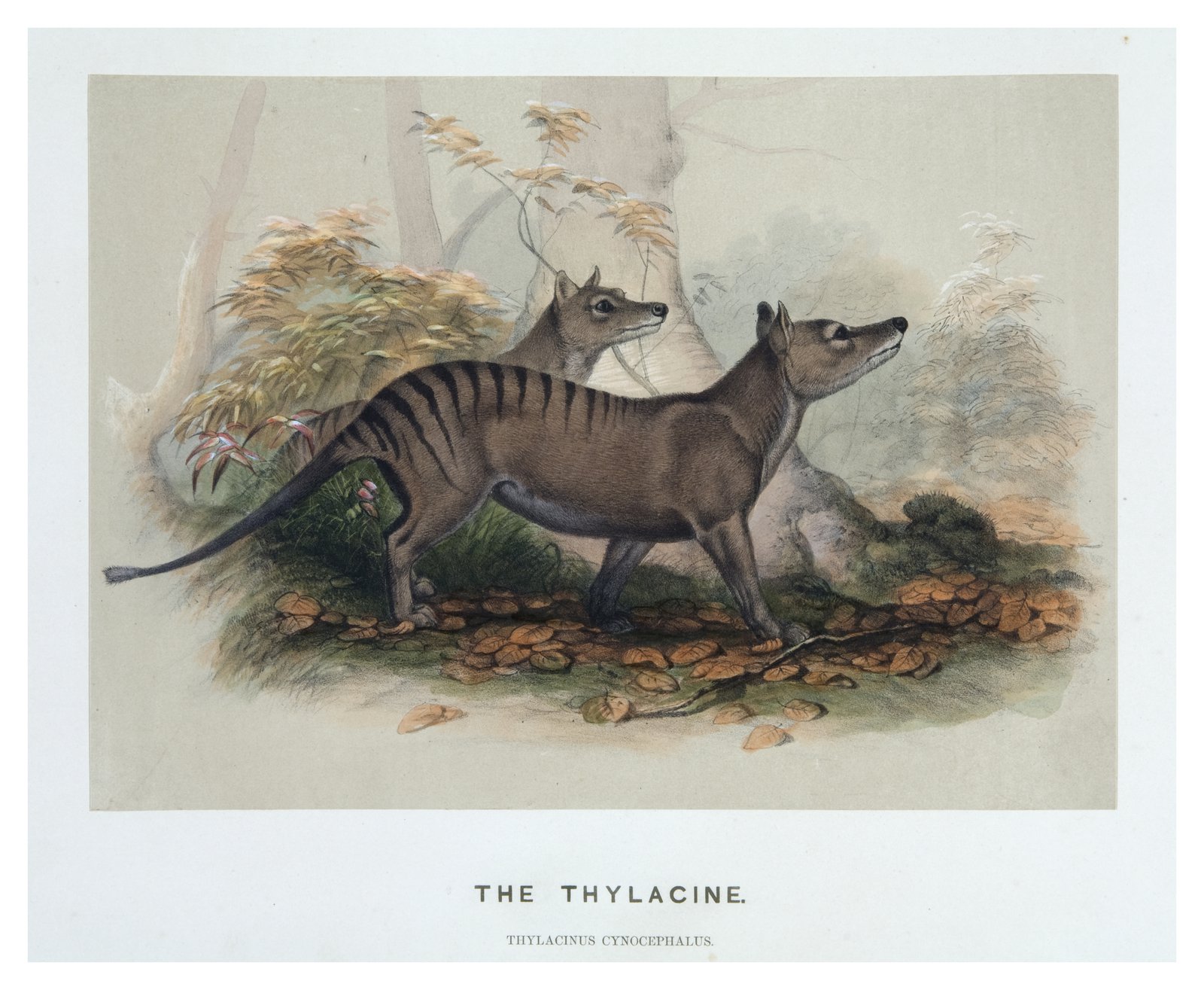

The Thylacine was sandy yellowish-brown to grey in colour and had 15 to 20 distinct dark stripes across the back from shoulders to tail. Although the large head was dog- or wolf-like, the tail was stiff and the legs were relatively short. Body hair was dense, short and soft, to 15mm in length.

It had short ears (about 80 mm long) that were erect, rounded and covered with short fur. Jaws were large and powerful and there were 46 teeth. Adult male Thylacine were larger on average than females.

The female Thylacine had a back-opening pouch. The litter size was up to four and the young were dependent on the mother until at least half-grown. Interestingly, males also had a back-opening, partial pouch.

Thylacine from Joseph Wolf's Zoological Sketches. 1861.

Image: Leone Lemmer© Research Library

What did it eat?

The Thylacine was mainly nocturnal or semi-nocturnal but was also out during the day. The animal moved at a slow pace, generally stiff in its movements. The Thylacine hunted singly or in pairs and mainly at night.

Thylacines preferred kangaroos and other marsupials, small rodents and birds. They were reported to have preyed on sheep and poultry after European colonisation, although the extent of this was almost certainly exaggerated. For example, this was perpetuated, intentionally or otherwise, by a series of famous photos taken by Harry Burrell.

Support our research

Help us to protect our vital natural and cultural heritage for generations to come. With your support, our scientists, explorers and educators can continue to do their groundbreaking work.

Make a donationWhere did it live?

At one time the Thylacine was widespread over continental Australia, extending north to New Guinea and south to Tasmania. In recent times it was confined to Tasmania where its presence has not been established conclusively for more than seventy years. In Tasmania the species was best known from the north and east coast and midland plains region rather than from the mountains of the south-west.

Thylacine skeleton, mounted, from the Mammals Collection at the Australian Museum.

Image: Carl Bento© Stephen R. Sleightholme

Why did it become extinct?

Although the precise reasons for extinction of the Thylacine from mainland Australia are not known it appears to have declined as a result of competition with the Dingo and perhaps hunting pressure from humans. The Thylacine became extinct on the Australian mainland not less than 2000 years ago. Its decline and extinction in Tasmania was probably hastened by the introduction of dogs, but appears mainly due to direct human persecution as an alleged pest.

Wet specimen of Thylacine pup in the Australian Museum's Mammal Collections.

Image: Stuart Humphreys© Australian Museum

Indigenous Peoples and the Thylacine

Aboriginal rock-paintings of Thylacine-like animals are recognised from northern Australia including the Kimberley region of Western Australia. They have also been found on walls or overhangs on exposed rock surfaces in the Upper East Alligator region of Deaf Adder Creek and Cadell River crossing in the Northern Territory.

There is evidence to suggest that Aboriginal people in Tasmania used the Thylacine as a food item.

Is there a fossil Thylacine?

Fossil thylacines have been reported from Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland.

Work at the Riversleigh World Heritage fossil site in north-west Queensland has unearthed a spectacular array of thylacines dating from about 30 million years ago to almost 12 million years ago. At least seven different species are present, ranging from small specialised cat-sized individuals to fox-sized predators.

The most spectacular find has been an almost complete skeleton of a thylacine from the AL90 site at Riversleigh. First glimpsed in 1996 when a limestone boulder was cracked to reveal part of the skull after 17 million years in a limestone tomb. After many months of intricate preparation the skeleton has been reassembled.

The fossil record of thylacines is a powerful reminder of how important it is to learn from the past the messages for the future. In Riversleigh times there were several species but by 8 million years ago only one species remained, the Powerful Thylacine, Thylacinus potens.

The modern Thylacine made its appearance about 4 million years ago.

A mummified carcass of a Thylacine has been found in a cave on the Nullabor Plain. It lived about 4 to 5,000 years ago, just before the Dingo was introduced into Australia.

3d model of skeleton and skin

This 3d model of a thylacine pup from the Australian Museum Mammalogy Collection combines Structured light scanning of the exterior of the specimen with Computed Tomography of the skeleton. The model is hosted on the Pedestal3D platform. Click '?' for instructions on navigating the model.

© UNSW, Biological Resources Imaging Laboratory and National Imaging Facility

View the model of the Thylacine on Pedestal3D for full screen and to access additional functions.